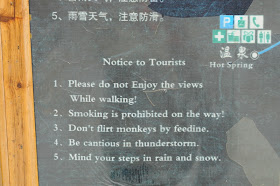

A naturalist visiting Mount Huangshan, no matter how tuned in he is to the fine points of plant and animal life, might be forgiven for failing to tear his eyes away from its magnificent and ever-changing scenery (yes, the final scene of Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon was filmed here). I had that difficulty myself, and have therefore spared my readers the same temptation by relegating my views of the mountain to a separate, earlier post. Hopefully, you have all, by now, had time to absorb these (and make plans, real or virtual, to see this great natural wonder for yourselves), and are ready to turn your attention to the life, animal and human, you can find along the trail. Meanwhile, take note of the sage advice posted above.

Just as a reminder, though, here is one last view of the ascent. Any visitor can follow in the paths of centuries of Huangshan tourists and climb the mountain from the bottom, but today most people (including your out-of-shape correspondent, his long-suffering wife and faithful guide) use the cable car.

That doesn't mean that we non-climbers are treated to a literal walk in the park once we arrive. The trails around the summit cover a vast distance, much if which you reach by climbing endless sets of stairs. Zhang suggested that we should descend, eventually, by a different cable route than the one we had taken to the top, and we didn't realize until we were well past the point of no return that this meant ten kilometers of ever-steeper staircases (past, of course, one magnificent view after another, so I am glad we did it).

Eileen observed afterwards that it was a good thing that we had tackled Huangshan at our age (or, at least, at mine); who knows how much longer we will be up to such a feat -- although the hordes of Chinese tourists crowding the trails included some very elderly climbers indeed.

Workers on the mountain don't have the luxury of the cable car. Every suitcase, box of food (for the hotels up top) and bag of trash has to be carried up or down the mountain on foot.

Tourists, though, have the additional option of hiring a sedan chair...

...creating an exhausting job opportunity for the chair carriers.

The forest on the heights of Huangshan is dominated by magnificent pine trees, many of them shaped by the wind into elegant natural works of art (and thereby providing the inspiration for many a human-created landscape painting). The dominant species is the Huangshan Pine (

Pinus hwangshanensis), found in several provinces of central China but first described from the mountain.

Besides the pines, we passed a number of fine stands of deciduous trees as we toiled along the summit trails. These are the leaves of Huangshan oak (

Quercus stewardii).

This is a Huangshan sorbus (

Sorbus amabilis).

We particularly enjoyed these lovely flowering dogwoods (

Cornus sp.). Of course all dogwoods flower, but species like this one surround their otherwise inconspicuous inflorescences with graceful, petal-like bracts.

I am not sure what this flowering tree is, but its flowers were particularly beautiful.

So were other flowers we found along the way: wild roses...

I believe this to be a viburnum of some kind...

This may be a viburnum too, clinging to a pocket of soil in the rock face.

This little jumping spider looks as though it had been carved out of Chinese jade.

Zhang, as usual, kept his eye out for birds, even among the often noisy crowds of mountain-watchers.

The most noticeable bird on Huangshan must be the Buffy Laughingthrush (

Dryonastes berthemyi). Bold, sociable and jaylike, it appears to have little fear of humans. It stays mostly at or below eye level, and we were able to get close to a number of what I presume were extended family groups.

I found this Grey-headed Canary-Flycatcher (

Culicicapa ceylonensis) was considerably harder to track down, though this is not usually a shy species. Its cumbersome English name reflects the fact that taxonomists have been a bit unsure about what to do with it; molecular studies have revealed that it's closest relatives are, rather surprisingly, in Africa, and both it and its kin have now been included in a 'new' bird family, the Stenostiridae or fairy-flycatchers.

Few countries besides China can boast, as one if its commoner birds, a creature as magnificent as the Red-billed Blue Magpie (

Urocissa erythrorhyncha). This one only let its head show out of the foliage, so you can't see its long and splendid tail.

The hotels on the mountain provided nesting sites for Asian House Martins (

Delichon dasypus).

Refuse tips along the trail provided exploring opportunities for this little squirrel, a ground-dweller despite it's impressively bushy tail. It is (I believe) a Perny's long-nosed squirrel (

Dremomys pernyi).

Butterflies included this danaid, which I believe to be a Chestnut Tiger (

Parantica sita).

This is

Araschnia doris, a specialty of China's central mountains.

To get to the second cable car station, we had to follow what turned out to be an increasingly steep spur trail leading, at times, through narrow passages between towering columns of rock.

Just before our final descent to the cable car, we had a close look at this fine male Asian Verditer Flycatcher (

Eumyias thalassinus).

This attractive little bird busily hopping about in a clump of low bushes was certainly the find of the day -- one of a small group of young Slaty Buntings (

Latoucheornis siemsseni), an obscure central Chinese endemic often thought to be different enough from the more typical buntings (

Emberiza) of the Old World to deserve its own genus.

The Slaty Bunting reminds me more of some of the New World "buntings" in the Cardinalidae than of its actual nearest relatives. We saw the birds quite late in the day, on the spur road to the second cable car -- justifying, for me (as if the scenery weren't justification enough) the extra effort we took to reach it.

At the end of our long day we descended, footsore and weary, via the last cable car to the mountain's foot. The woods at the bottom were decorated with clumps of immense bamboo.

Here I found a remarkable tree. There are only two species of tuliptree in the world, one -- the yellow-poplar or American tuliptree (

Liriodendron tulipifera) in eastern North America -- and the other in China, a distribution matched by a number of plants (including the tuliptree's near relatives the magnolias) and by such peculiar and ancient animals as paddlefish, giant salamanders and alligators. This is the Chinese tuliptree (

Liriodendron chinense), its oddly truncate leaves immediately recognizable, though they are larger and more dramatically lobed than those of its American cousin.

Finally, just before we drove back to town for an exceedingly well-earned rest, I was able to get my closest view yet of a Collared Finchbill (Spizixos semitorques), one of China's most distinctive and handsome bulbuls.